Victorian in appearance.

Victorian in appearance.

Valiant in the face of danger.

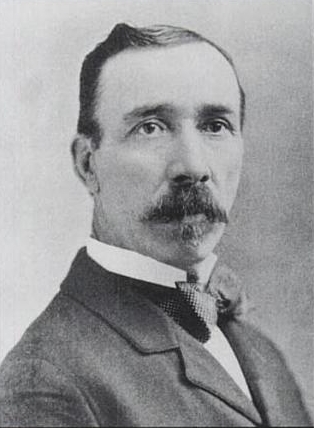

James Root, Engineer

More than 150 people climbed onto Root’s train as he drove five miles in reverse to reach tiny Skunk Lake, north of Hinckley. Though badly burned, he remained at the throttle until the train reached its destination.

Their actions saved hundreds.

Thomas Dunn, Depot Agent

As the fire approached, Dunn stayed at his telegraph, calling for help and sending words of warning along the wires. The final words he transmitted were, “I think I’ve stayed too long.”

Tom Sullivan, Conductor

Making his way through the burning train, choked and blinded by smoke, he still did his best to comfort his passengers as the train raced to the relative safety of the water.

John Blair, Porter

As people climbed from the train at Skunk Lake, Blair assisted them and made repeated trips back to the burning coaches to rescue children. He was the last one to leave the doomed train when he was certain all passengers were off.

William Best, Engineer

When given instructions to leave, Best set the air brakes of his train instead, to hold the train so more could escape. It will never be known how many lives were saved because Best held a firm grip on the air brakes for a few more crucial moments.

Edward Barry, Engineer

Barry ran his train in reverse to escape the fire, relying on two brakemen to flag him safely across burning bridges. His eyes were badly affected by the smoke, and by the end of the trip he was almost blind.

Root’s Engine

Literally the last train out of town, the Saint Paul & Duluth Railroad train took many to the relative safety of Skunk Lake, north of Hinckley. A sign on the Willard Munger State Trail marks Skunk Lake today.

The Pit

Many were saved by submersing themselves in what little water remained at the bottom of a gravel pit along the tracks. You can visit the pit today, which is now a memorial park.